The unstoppable rise of the cupcake over the past five years has been analysed in terms of retro-food chic and nostalgia, the infantilisation of Western civilization, the triumph of appearance over substance, and even American political culture. After all, a cupcake is both democratic (one equally-sized cupcake each) and libertarian (there is no imperative to share and everyone can have a different flavour), in marked contrast to the communal cake.

Cupcakes by Cupcake Royale, Seattle

Now, according to Dr. Kathe Newman, a lecturer at the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, it turns out that a spatial analysis of cupcake proliferation could also reveal the flow of capital investment in cities.

In an interview with Cakespy.com, Dr. Newman explained that she is currently building a collaboratively sourced map of New York City’s cupcake shops. In September 2009, Dr. Newman and her students will use this map to embark on a “Tour de Cupcake” – a fieldwork (and tasting) exercise designed to test her theory that cupcake shops can provide a more accurate and timely guide to the frontiers of urban gentrification than traditional demographic and real estate data sets. Finally, she intends to submit a paper summarising her findings to the Urban Affairs Review.

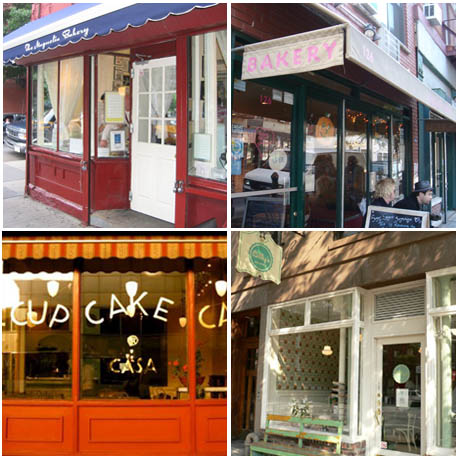

Image: NYC cupcake bakeries. From left to right and top to bottom, Magnolia Bakery, widely regarded as the cupcake trend mothership, Sugar Sweet Sunshine, Cupcake Café, and Billy’s Bakery.

Of course, culinary markers of class transformation change over time. Indeed, the New York Times suggests that those on the cutting edge of the baked goods index have already moved on to whoopie pies, while not so long ago, Dr. Newman’s students might have been tracking gourmet coffee and frozen yogurt shops.

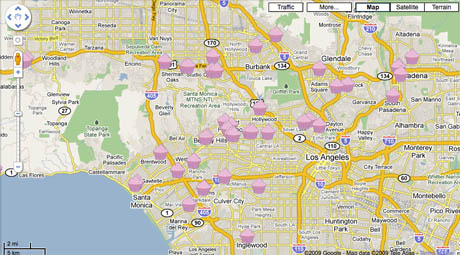

The Great L.A. Cupcake Map, created by Elina Shatkin for the L. A. Times to aid consumption rather than study – but nonetheless, a useful tool to visualize, for example, the gentrification of Culver City, now spreading southwards down the 405.

In fact, it would be interesting to overlay Dr. Newman’s diagnostic mapping technique with a timeline of the food trends of gentrification. From Le Creuset cookware and dine-in kitchens to gastropubs and gourmet food trucks, shifts in food type and availability are one of the most effective ways of remaking urban space. Food trends such as the rise and fall of the panini or the ascendance of fusion cuisine also provide a fascinating insight into the larger narratives and microhistories of popular culture. (Just as an aside, I can see the TV series and cookbook spin-off now – Gentrification: Half a Century of Aspirational Cuisine.)

Combine the two, over time, and you might well uncover unexpected appropriations, unspoken defensive and colonising behaviours, as well as subtle shifts in the self-image and motivations of the “pioneering” urban middle-classes. On closer analysis, London’s viral cappuccino bloom in the early nineties might well shed interesting light on the unacknowledged after-effects of post-Thatcher public-private financing initatives.

Meanwhile, who is to say that cupcake gentrification might not function as cause, as well as effect? Could urban planners “seed” depressed areas with gourmet delis and boutique coffeeshops, in order to lure in a gentrifying vanguard of artists and hipsters? Forget former NYPD chief Bill Bratton’s “Fixing Broken Windows” theory; in this view, what would really turn around certain neighbourhoods is a state-funded injection of artisan bakeries.

I’m reminded here of former L.A. Laker’s superstar Magic Johnson‘s pledge to provide 50% of the financing needed to locate Starbucks outlets in underserved communities: his Urban Coffee Opportunities partnership has already opened 90 new stores and counting. Johnson’s development corporation works on the rationale that bringing retail franchises such as T.G.I. Fridays, Loews Cineplexes, and Starbucks coffeehops to low-income urban neighbourhoods will create jobs, encourage other businesses to invest, and provide residents with local amenities – and thus far, he seems to have been relatively successful. In an Urban Land Institute article honouring Johnson’s achievements as a community builder, Marcia Lamb, co-executive director of the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City, a nonprofit group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, described the process thus: “They are, in effect, mainstreaming these tough urban markets, and everybody benefits.”

Others refer to “death by cappuccino” and the “just add culture and stir” school of thought, noting that simply parachuting in upscale food franchises results in a depressingly homogeneous “geography of nowhere,” and privileges an ultimately unsustainable culture of leisure and retail consumption over production. And of course, an influx of middle-class gentrifiers into a low-income neighbourhood does not come without its own problems. Nonetheless, it’s interesting to wonder whether all along, investing in a few locally-owned cupcake shops might have a more positive impact than blanketing our cities in CCTV.